April 11th - 12th 2026

Best of Festival

Best Documentary

Feature

Best Foreign Documentary

Best Documentary

Short

Youth Jury

Clean Power City Champion Award

Congratulation Winners

Directed by

Xinyan Yu and Max Duncan

When a massive Chinese industrial park lands in rural Ethiopia, a dusty farming town finds itself at the new frontier of globalization. The sprawling factory complex’s formidable Chinese director Motto now needs every bit of mettle and charm she can muster to push through a high-stakes expansion that promises 30,000 new jobs. Ethiopian farmer Workinesh and factory worker Beti have staked their futures on the prosperity the park promises. But as initial hope meets painful realities, they find themselves, like their country, at a pivotal crossroads.

Filmed over four years with singular access, Made in Ethiopia lifts the curtain on China’s historic but misunderstood impact on Africa, and explores contemporary Ethiopia at a moment of profound crisis. The film throws audiences into two colliding worlds: an industrial juggernaut fueled by profit and progress, and a vanishing countryside where life is still measured by the cycle of the seasons. And its nuance, complexity and multi-perspective approach go beyond black and white narratives of victims and villains. As the three women’s stories unfold, Made in Ethiopia challenges us to rethink the relationship between tradition and modernity, growth and welfare, the development of a country and the well-being of its people.

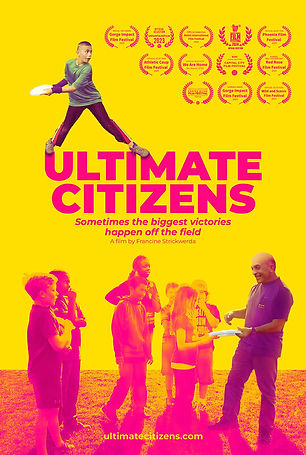

Directed by

Francine Strickwerda

ULTIMATE CITIZENS is not a movie about Frisbee. The “flat ball” is one of many tools that Jamshid Khajavi, the film’s protagonist, uses in his work as a primary school coach and counselor. A fiery, funny 65-year-old Iranian immigrant and ultra-athlete, Jamshid does some of his best work on the playing field with his students, the children of refugees and immigrants.

In a season of healing, Jamshid coaches two intrepid 11-year-olds, Nyahoak, whose South Sudanese parents came to the U.S. as refugees, and Pio, whose Samoan parents wanted a better a life, but experience homelessness. Jamshid teaches the kids about life on their way to compete in the world’s largest youth Ultimate Frisbee tournament.

The story unfolds at Hazel Wolf K-8 School in Seattle, a city known for its high-tech companies and $7 coffees. It’s also an America where many families quietly struggle to afford housing and survive.

Jamshid’s efforts to build community where all kids can thrive are heroic. But in this story, it’s the parents who work low paying jobs around the clock, and their first-generation Americans kids, who become champions long before the tournament even begins. They save themselves, with a little help from a compassionate counselor in a supportive school.

At a time when schools are on the frontlines of America’s culture wars, some politicians and parents are fighting the work of counselors like Jamshid. He teaches social emotional learning and sex education. He talks with families about grief and loss, and helps remove barriers to learning and belonging.

Today there are roughly 100 million forcibly displaced people around the world – more than at any time in modern history. The plight of these asylum seekers is increasingly met with anti-immigrant policies and violence. This film showcases the potential of what immigrants like Jamshid and his students can bring into our communities instead of viewing asylum seekers as a drain on resources.

Underneath the “David vs. Goliath” tournament narrative that builds toward the film’s climax, this documentary offers an antidote to “us versus them” political headlines with a heartwarming vision of a more welcoming America. You often hear Jamshid saying to people, “I’m so glad you’re here,” and he means it. For almost 40 years, Jamshid has taught children how to be “ultimate citizens” – to look out for themselves and each other, and to choose inclusion over exclusion. He and the kids show how to do the hardest work of all – to find their way forward, together.

Director

Davoud Abdolmaleki

Growing up in an oppressive culture in Iran, Davoud saw firsthand the lowly status that was imposed on women compared to men and the lack of freedom of expression that they were given. It’s what drove him to give women a voice through his documentary film making.

This led Davoud to direct From the Cradle to the Grave, a 2024 Free Speech Film Festival Official Selection. In the film, he documents interviews with students at a girls’ high school who have lived the answers to two important questions: “Are we responsible for our destiny?” and “Do we have the ability to change the circumstances of our lives?”

Davoud was drawn to create the film because of his love for his grandmother, mother and two sisters. He wanted a way to voice his reaction to the way that women were placed under what he referred to as “the command and prohibition of the men of the family.” He said that the social and political changes that happened in Iran created difficult conditions for women and shaped his desire to tell women’s stories in his films.

“Women were always under the supervision of men and the rules of family and society. Their mistakes were bigger than men’s mistakes and their role in the family was always considered less than that of men. I did not like this look on women,” he said. “The condition of women in a society shows well the human rights situation of the people of a country. Women in Iran, as I saw them, were always bad. Everything that was imposed on them under the name of education and upbringing in the family, in schools, in the society and by laws, alienated women from their nature. I always criticized the wrong way of teaching in schools. Educational programs tried to make students a fake human being who follow patterns and conventions and are obedient. These educational programs were not compatible with nature and human nature and did not help to improve the condition of women.”

As a child growing up during a time of war, when the electricity in his home was constantly being cut off, Davoud developed a fascination for the contrasts of darkness and light and how it changed ones perceptions of the people around them.

“I was excited by the darkness of the environment and the light of the candles that cast the shadows of people and objects on the wall. I looked at the faces of family members in the dark. Their faces were visible for a short moment by the candlelight, and then the darkness hid their faces” he said.

Being so aware of this difference between darkness and light in people drove Davoud to be a big fan of film and cinema. As a boy, he would wait in long lines to purchase tickets to the cinema. Since his parents wouldn’t give him money to buy a ticket, he started his own little side hustle where people pay him to stand in the long lines and purchase tickets for them and he would use that money to buy his own ticket. The demand at the cinema was so great that no one could watch the same movie twice in one day. But Davoud would hide under the seats in the theater in between screenings to get the chance to watch a film a second time.

To Davoud, the cinema is where he came alive.

“When we were first taken to a mosque to watch a film, I was amazed at what I saw. I was fascinated by the images. It was just what a dreamer needed. In that darkness, I sometimes looked at the moving pictures and imagined myself in the place of the movie characters,” he said. “From then on, cinema became everything for me. A refuge for my loneliness, a place to stimulate my imagination and a place to experience all kinds of emotions on the faces of the audience as they stared at the big screen.”

As Davoud grew up, his idyllic life at the cinema was replaced with a sensitivity to the negative social issues he saw all around him: war, bad economic situations, unwanted political and social changes, poverty and suffering. This led him to realize that there was a stark difference between fiction and reality and he wanted to be a realist.

“Cinema became the border between reality and dream for me, where I could think about the concept of reality and fantasy. In general, the artist should be the most realistic realist and be someone who shows films exactly as they observe it and not in a way that others want them to.” he said.

By the time he entered the University of Tehran Faculty of Performing Arts and Music, Davoud knew documentary films were his calling.

“I was critical of false and deceptive fictional films. They had no function other than vulgar entertainment, making people’s lives look good, lies and propaganda, and this is still the case in Iranian cinema,” he said. “So, among the large number of fake fictional films, I preferred documentaries that depicted the real lives of people. I went this way. After writing many scripts and editing and shooting many films for others, when I felt that my films might mean something to others, I decided to focus on my own ideas. The first important idea that was in my mind for several years was to make a film criticizing the education system and depicting things that are not seen in girls’ schools.”

This is how From the Cradle to the Grave began. Davoud said he drew on his past experiences and observations and the emotional pull he felt watching women suffer to create this documentary focused on school, ideological training and identity.

“We started filming with the question that the teacher asks the students while teaching: ‘Are we responsible for our destiny?’ ‘Do we have the ability to change our life circumstances?’ The students of a girls’ high school told us the answers to these questions not based on the lessons of the teachers or what is written in the textbooks, but based on their life experiences in the real world,” he said. “We gave the students a lot of opportunity in front of the camera to reach the moment that revealed their truest reality. When the camera would turn on, we’d remain patient and wait to record the moments when all their fears would go away and they would be their true selves as much as possible.”

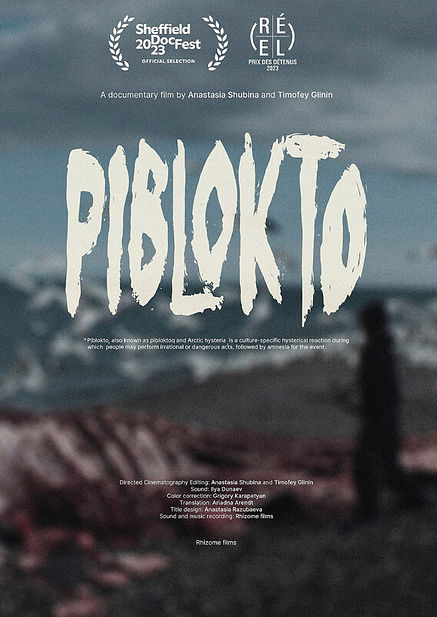

Directed by

The film was born as a result of our long-term interest and research into the traditions of the North, shamanism and folk collective unconscious. One of the directors of the film, Anastasia Shubina, an anthropologist and philosopher, has been studying Eastern culture and shamanism since 2016, and our last documentary “The art of falling apart” was dedicated to reindeer shamans in the North of Mongolia. Through cinema, we explore the cultural traditions of indigenous peoples who, despite being part of Russia (as they were colonized in the past by the Russian Empire and then the USSR), retain their cultural identity and their own patterns of thinking.

The main cultural event for the Chukchi and Eskimos has traditionally been a shamanic ritual, an event of symbolic death, during which the animal and human spirits tear his body apart and eat him. It is believed that this initiation gives the shaman control over the spirits, and for the people of his community, it is an entry into the cycle of life and death, where the dead and spirits are part of reality.

In our film, we used the sound of a shamanic ritual that we recorded during the expedition. It became not only the soundtrack, but we also structured our film according to the rhythm of the ritual. Its dramaturgy is based on repetitions and cycles and reflects the rhythm of life and the mythological stories of the Northern peoples. The life of the Chukchi and Eskimos is strongly connected with the cycles of nature, repeats itself day by day, and revolves around the sea hunting for big marine animals: whales and walruses.

People living in Inchoun and Uelen villages, on the coast of the Arctic Ocean, are in complete isolation from the rest of the world. Food is brought to their stores by ship once a year, and sea hunting is the only way to survive. For them, hunting and killing animals is just a routine, necessary to get enough food.

The film title “Piblokto” (Arctic hysteria) is a disease that affects people in the Far North, similar in its manifestations to shamanism. A person sings in non-existent languages, repeats the same actions, and can perform aggressive, seemingly meaningless actions. (From the point of view of an external observer, this is similar to the behavior of a shaman during a trance).

However, the phenomenon of “Piblokto” is controversial. On the one hand, it reflects cultural events unique to the North and its traditions. On the other hand, the term “Piblokto” (despite the seemingly authentic sound) does not exist in the Eskimo or Chukchi language and was invented by external onlookers. Moreover, the indigenous people themselves do not always consider this condition a disease. In the film, we tried to keep a sense of this ambiguity

While filming, we spent several months in the remote villages of Chukotka, next to the Bering Strait, in the summer of 2020. For us, this film is an opportunity to touch the otherness, trying not to impose our own patterns of thinking on their lives, to allow the rhythm and atmosphere of the film to be born from the people's inner lives and their own cultural practices.

Service Name

Directed by

Matthew R. Brady

The earth is rapidly approaching a sixth mass extinction event, with a quarter of all species under threat. However, there is still hope. Armed with a radical new vision known as ‘rewilding’, follow the world’s top environmental leaders on a spectacular journey across six continents as they work to rebuild ecosystems, restore biodiversity, and even transform lives.

From the cloud forests of Rwanda to the California coast, this bold new approach to wildlife conservation is not without its challenges. However, it may just be the solution to finding a sustainable balance between our delicate natural world and the demands of a growing human population.